1531424679000

Ethiopia: The Past, Present and Future of Coffee

I think a lot about their hands. The hands of farmers I met in the country where coffee was born. Hands, brown like mine and browner still, coaxing saplings from rich soil, pulling bright red berries (called “cherries”) off thin branches, transforming fruit into the precious liquid that propels me and millions of others into the day.I arrived in Ethiopia in the middle of the night. The air was thin and cool; the city, hazy and quiet, giving no indication that it was the origin of the substance that caffeinates the world.Coffee is our collective drug of choice: We drink more than 2.25 billion cups of coffee globally, with Canadians among the world’s top consumers.Yet, despite this affinity for the beverage, most think of Starbucks as the source of coffee, not a distant country nestled in the Horn of Africa.Ethiopia, however, represents the past, present, and future of coffee. It is not only where the Coffea arabica plant first blossomed, but also the place that gave the world methods of coffee preparation, along with a culture of community around the beverage.And of all the coffee-growing regions, Ethiopia holds the greatest diversity of coffee plants — what is needed to sustain the crop well into the future.

1530223519000

The Ugly Truth about Arts Institutions Led by Women of Color

As the founder and executive artistic director for the (BATC) in Dallas, Texas, I experience racism, sexism, and classism almost daily. It’s no secret that racial and gender disparity is a chronic problem for women in leadership at arts institutions in the United States, but for women of color, there is a severe, unconscious level of prejudice.I’m so grateful for the on women artistic and managing directors in the (LORT), commissioned by . It not only gave me the lexicon to talk intelligently about the issues I was experiencing, but, more importantly, it made me feel less like a martyr.The study found zero women of color as executive directors in LORT, the largest professional theatre association in the United States, and only one woman of color as an artistic director. This is a dismal reality for women like me who are founders of their own theatre company, hoping to transition to jobs at LORT theatres in the future.The ugly truth, which was revealed in the study, is that "hidden behind a gender- and race-neutral job description is an expectation, grounded in a stereotype, of what a theatre leader needs to look like: white and male."White men are the long-standing majority of those in top positions, which translates to who funders trust to provide financial resources, who the media decides to give a platform to, and who board members select to lead their organizations.

1528944210000

Faces of Afro-Argentinians

Stunning Photos of the African Presence in Argentina

1527871072000

Black Montreal: A Brief History

Black Montreal is diverse and growing.Broadly speaking, there are two prominent groups with little mixing between them: the older segment of the community has roots in Canada, the United States and the English-speaking West Indies while more recent Black Montrealers likely originate in Haiti or French-speaking African countries.Canadian Black history started long ago. Some historians believe that Libyans may have visited Canada in 500 A.D. and that Africans landed here in the 14th century.The first recorded Black visitor was Matthew da Costa, in 1606, who is listed as Champlain’s translator, having learned a native language, Mic Mac, on a previous voyage.It would be a long time between this visit and the beginnings of a real Black community since slavery, of both Black and natives, was legal in Canada until 1834.Blacks began settling in this country during the American revolution following British promises of freedom and land. They could be considered Canada’s first refugees and were followed by many who escaped during the American Civil War. They first settled in Nova Scotia or Ontario, with some then moving to Montreal.

1527768000000

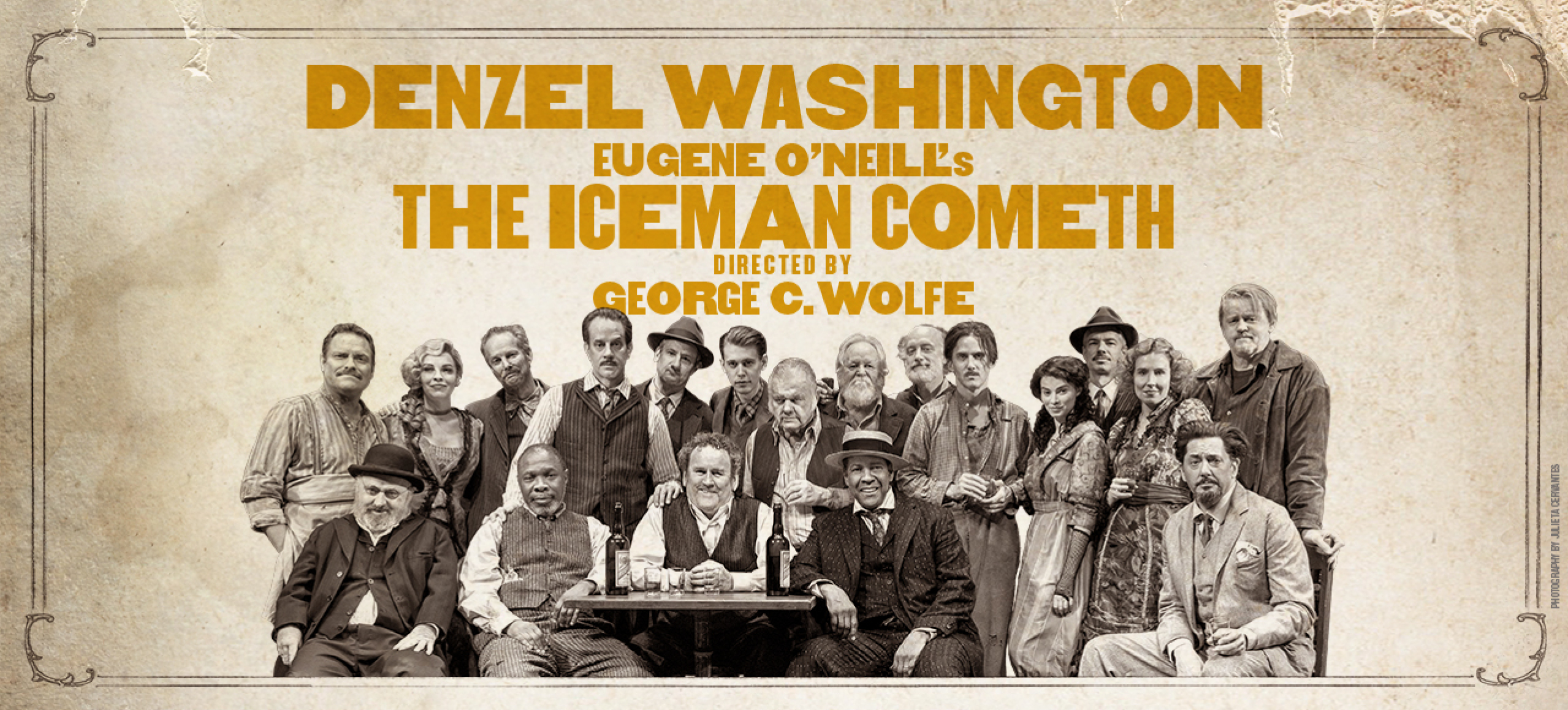

On-And-Off Black Broadway Shows You Must See

On and off Broadway plays and musicals written, directed, featuring, or starring Black cast members and other creatives.

1526016449000

Using Storytelling and Dance to Transform a Community Space

It seems fitting the inaugural iteration of Kaimera’s SPACES was in Harlem, the home of many twentieth century cultural innovations. Currently in talks with presenters in Bulgaria, France, Germany, Greece, India, Kenya, Romania, as well as New Orleans and Oakland in the US, SPACES is on track to become a global endeavor.Between the co-creators of SPACES—, , and —English, Spanish, French, Italian, Russian, and Portuguese are spoken. With their SPACES project, offers a new piece of place-specific, rather than site-specific, theatre.At the heart of SPACES is a curated performance of a diverse group of local storytellers, inviting its audience to connect with real people in an actual place—an experience theatre is primed to provide in our increasingly digitized world.I saw SPACES: Harlem in June 2017, when it was presented as part of the multi-disciplinary Harlem Arts Festival, and housed in the Mt. Morris Ascension Presbyterian Church across the street from Marcus Garvey Park.Arriving at a check-in table just inside one of the entrances to the historic church, audience members were each assigned a color, and a corresponding piece of string was tied onto our wrists. Thus tagged and separated from our companions, we were directed to gather within chalk circles in front of the steps that matched our string.As we chatted with strangers standing in our chalk circles or silently enjoyed the music wafting over from across the street, a drummer appeared on the top stair and began to play.

1525953600000

Harlem Renaissance in the American West

The study, The Harlem Renaissance in the American West, shifted the focus of the Harlem Renaissance away from New York City’s Harlem to the cities and states of the American West, and away from literature to the full range of the creative arts.It is inspired by the broadened view of the early twentieth century African American literary and artistic movement that has established that while the Renaissance was centered in New York, it was a national phenomenon.The traditional view held that while few of the participants in the Harlem Renaissance were from Harlem, all spent considerable time there. We determined that while most of the writers and artists associated with the movement spent significant time in Harlem, and most considered themselves part of the Renaissance, many also spent long periods of their careers away from Harlem, and some spent most or all of their creative careers outside of New York.The black experience in the West clearly establishes that not only did many participants in the Harlem Renaissance have western roots or western connections but in communities across the West African Americans were involved in black art, literature, and music both as consumers and as artists themselves.In her 2008 book, From Greenwich Village to Taos: Primitivism and Place at Mabel Dodge Luhan's, Flannery Burke observed that the term Harlem Renaissance "is a misnomer that fails to acknowledge the cultural activities of African Americans prior to the 1920s and in areas outside New York City." Our volume pursues Burke's comment by investigating the West. Given the relatively small African American population in the West, a disproportionate number of black writers and artists had roots in the West before they came to Harlem.

1525694400000

Colonel Charles Young: Black National Park Superintendent

When the new military superintendent for the summer of 1903 arrived in Sequoia National Park he had already faced many challenges. Born in Kentucky during the Civil War, Charles Young had early set himself a course that took him to places where a black man was not often welcome.He was the first black to graduate from the white high school in Ripley, Ohio, and through competitive examination he won an appointment to the US Military Academy at West Point in 1884.He went on to graduate with his commission, only the third black man to do so. Later he would remark that the worst he could wish for an enemy would be to make him a black man and send him to West Point.His military career progressed in the cavalry. In 1903, he was serving as a Captain in the Cavalry commanding a segregated black company at the Presidio of San Francisco when he received orders to take his troops to Sequoia National Park for the summer.In May, 1903, Sequoia National Park was already thirteen years old but still under-developed and hard to visit.Since 1891, the management and development of the park had been the responsibility of the US Army, but owing to a lack of Congressional funding almost nothing had been done.The biggest lack in the park was an adequate wagon road to the Giant Forest, the home of the world's largest trees.Army work on a road had begun in the summer of 1900, but progress had lagged. In three summers barely five miles of road had been constructed.

1522111126000

Black Pain on Stage

In Relevance, a play by JC Lee, black feminist author Msemaji Ukweli, who wrote a book about her sexual assault, explains why she changed her name from Tiffany Hall, and omitted from her biography any mention of her education at an expensive boarding school: Opportunity for African Americans, the character says to a white literary agent, “does not happen without indulging the white predisposition for black pain. It’s the toll you demand for our success, because it confirms both your superiority and our worth should we overcome it.”Black pain, as it happens, is the subject of a surprising number of recent plays in New York. Sometimes the pain is expressed only in passing, in a scene or an anecdote.But in other current works on stage, it is a central theme, most often chronicling violence against African Americans—seldom in easy or expected ways.To Harry Lennix, the expression of such pain in the past too often has taken the form of what he calls “suffering porn.”As he told me , “frequently I find the stories about black people’s servitude and pain are a little indulgent, or masochistic, and exploitative.” Lennix, a well-known actor, is making his New York directorial debut in a play by LeKethia Dalcoe entitled A Small Oak Tree Runs Red, which is running at the through 4 March 2018.It is inspired by a true story that occurred in Valdosta, Georgia, in 1918, when at least a dozen African Americans were lynched within a few days of one another, and focuses on one of the victims, Mary Turner, who was twenty years old and eight months pregnant. She was lynched for speaking out against the lynching of her husband the day before.

1520389398000

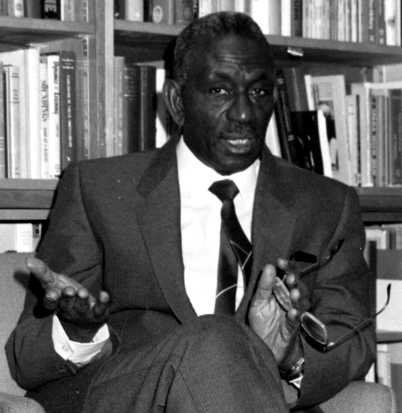

Cheikh Anta Diop: The Pharaoh of Knowledge

Cheikh Anta Dip was born in 1923 in a small village in Senegal, Caytou. Africa is under European colonial rule which took over the Atlantic slave trade begun in the 16th century. The violence to which Africa is subjected is not of an exclusively military, political and economic nature. Theoricians ( Voltaire, Hume, Hegel, Gobineau, Lévy Bruhl, etc.) and European institutions (the Institute of Ethnology of France created in 1925 by L. Levy Bruhl, for example), apply to legitimize on the moral and philosophical level the decreed intellectual inferiority of the Negro. The vision of an ahistorical and timeless Africa, whose inhabitants, the Negroes, have never been responsible, by definition, for a single fact of civilization, is now imposed in the writings and anchored in the consciences. Egypt is thus arbitrarily attached to the East and the Mediterranean world geographically, anthropologically and culturally.It is therefore in a particularly hostile and obscurantist context that Cheikh Anta Diop is led to question, by a methodical scientific investigation, the very foundations of Western culture relating to the genesis of humanity and civilization. The rebirth of Africa, which involves the restoration of historical consciousness, appears to him as an unavoidable task to which he will devote his life.

1519128000000

New Orleans: The Second Line Culture

By Rashid Booker The name 'Second Line' is an urban social tradition for the African-American youth of New Orleans. Being a “Second Liner” is something that the youth look forward to. It is full of energy and you’re right behind the band as they strut down the narrow streets.Strutting and dancing with your umbrella in hand to the beat of “Street Parade.” Just name any African-American so-called jazz “ great,” who came out of the great music city, and he/she has paid their dues to the Second Line."The Second Line is a symbol of New Orleans,” said Zohar Israel, who’s a native, “its excitement and tradition. African Americans affliction, a gift to New Orleans."To understand the Second Line, you must research the historical background of the so-called Jazz Funeral. The term Jazz Funeral can be very confusing; it's a contradiction. How can anyone experience the excitement of this great art form and at the same time lay your loved one to rest?Realizing the term is foreign and can be difficult to understand, but, nevertheless The Second Line is part of New Orleans' rich culture. American heritage came from New Orleans, Louisiana, by way of the African Americans who immigrated to our country in chains.

1518868800000

Destinations for African American Heritage in Philadelphia

From Colonial times, to the struggle for freedom and civil rights to the present, Philadelphia has served as home to African American abolitionists, activists, artists, music legends and religious and cultural institutions which helped fashion Philadelphia and the nation.

1518835031000

Resurgence in America’s Roots Region: Towards A Cultural Foundation of Activism and Engagement

“If theatre means anything anywhere, it should certainly mean something here,” Dr. Doris Derby the night the Free Southern Theater (FST) was born.Founded in 1963, the FST filled a vast cultural and activist void in the deepest Southern states. Dr. Derby, John O’Neal, and Gilbert Moses, organizers with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), theorized that civic organizing necessitated an authentic cultural undergirding.Their vision brought forth a theatre that was as unique to the Southern African-American experience as blues or jazz—a theatre for free thought, aesthetic beauty, and protest.FST engaged with churches, developed a linguistic style that aimed to complement grassroots political action with rural culture, and—perhaps most importantly—committed to communities through creative dialogue.“The Free Southern Theater was a tool, a creative tool, to teach the people that we performed for about what…they are expected to have as American citizens and were being denied in some way,” said FST actor Seret Scott who was interviewed by Michael Lueger for HowlRound’s Theatre History in 2017.In the ’80s, the FST was reorganized into , a still-active and interrogative company in New Orleans named after a popular and populist, FST storytelling character, Junebug Jabbo Jones, who had been performed by O’Neal.The New Orleans-based poet-educator-actor-activist Michael “Quess?” Moore, in his published on this site, credits the legacy of the FST, Junebug, and John O’Neal with introducing him to “an alternate world of sorts, where activism met acting” and inspiring his work.But despite FST’s legacy of inspiring artists and their impact in subsequent iterations, they were struggling to survive as a theatre in an economically oppressed region.In an interview from 1987 in the Tulane Drama Review, Thomas Dent, who took over as artistic director of FST in 1966, addressed the financial limits the FST faced at the time.In addition to financial pressure, in ‘66 some of the FST actors and organizers had become philosophically disillusioned, as evidenced in Gilbert Moses’s , and a from Thomas Dent to the FST board of directors in which Dent calls out ongoing and longstanding conflict in the theatre. Time for a New Southern TheatreI went down [South] in January of 1969. I was a young, young person and just out of school…these young girls were standing there looking at me and talking to me, because to many of them I looked much the same as they did in terms of how old I was.And they were talking to me about New York and about Washington, DC, which is where I'm originally from. …I mentioned I had been at the university in New York and that I had left to come down to work with the group and to work with people like them. And there was a silence and one young girl said, ‘You left a college to come down here and be with us to do this?’—Actor Seret Scott.

1518564559000

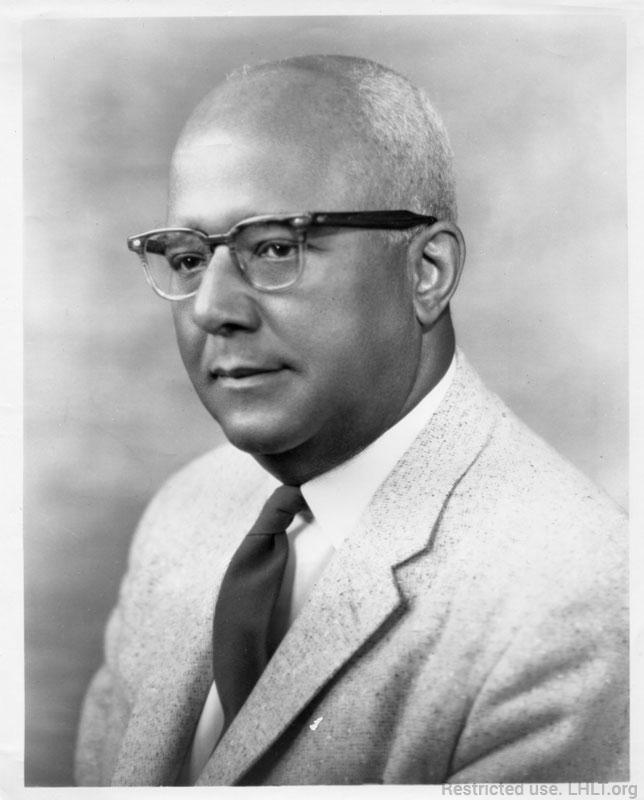

William Leo Hansberry: Architect Of African Studies In America

Historian and anthropologist, William Leo Hansberry began his college education at Atlanta University, but (at the urging of W.E.B. DuBois) he transferred to Harvard in 1917. Based on his reading of classical texts and his study of archeological evidence, Hansberry became convinced as an undergraduate that sophisticated civilizations had existed in Africa–especially in Ethiopia–for centuries prior to the rise of the Greeks and Romans in Europe.He pursued that premise for the rest of his life.A circular letter announcing his desire to develop courses in African civilization landed him a temporary job at Howard University in Washington D.C., following his graduation from Harvard in 1921.There he quickly built his new program into one of the most popular undergraduate majors on the campus, and he hosted international conferences to stimulate the study of ancient and medieval African societies.

1518523200000

Black Manhattan's Long-Gone San Juan Hill

In the early 20th century, Lincoln Square’s streetscapes hugged the ground with rows of tenements and brownstones, punctuated by warehouses and industrial lofts. Its residents were mostly working classand poor, with a notable contingent of artists and bohemians. On its eastern fringe stood a variety of theaters and music halls. Squeezed into the middle, roughly from 59th to 65th Streets between Amsterdam Avenue and the 11th Avenue railroad tracks, was San Juan Hill, one of the largest black neighborhoods in Manhattan before the rise of Harlem.Historian Marcy Sacks, author of “Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before WorldWar I” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). As I stand outside two of the neighborhood’s last old houses, 242-244 West 61st Street, with new construction looming beside them.San Juan Hill’s “tall,monotonous tenements” were “the worst type which the city affords.” Up to 5,000 people lived jammed into a single block; beds were often used in shifts, shared by boarders. Neighborhood was named to honor the United States Army’s black 10th Cavalry, which fought at the battle of San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War in 1898.

1517895001000

Journalist And Historian Drusilla Dunjee Houston"To Die Is To Gain"

Much has been written about New York's Harlem Renaissance, and its black literary and visual artists. The reality: the black renaissance occurred throughout the country, including Oklahoma City. Drusilla Houston, journalist and historian, held her own in a world that included other public intellectuals like Joel A. Rogers ("Sex and Race, Vols. I-III", "Nature Knows No Color Line", "100 Amazing Facts About the Negro" and a column on Negro History in the Pittsburgh Courier).Houston was born at Harper's Ferry, Virginia in 1876. In 1892, her family moved to Oklahoma. Both parents were religious and politically active, passing on their traits to the children. They also encouraged education and entrepreneurship.

1516918577000

The Black Arts Movement II:Theory and Practice

Part II: Theory and Practice The two hallmarks of Black Arts activity were the development of Black theater groups and Black poetry performances and journals, and both had close ties to community organizations and issues. Black theaters served as the focus of poetry, dance, and music performances in addition to formal and ritual drama.Black theaters were also venues for community meetings, lectures, study groups, and film screenings. The summer of 1968 issue of Drama Review, a special on Black theater edited by Ed Bullins, literally became a Black Arts textbook that featured essays and plays by most of the major movers: Larry Neal, Ben Caldwell, LeRoi Jones, Jimmy Garrett, John O'Neal, Sonia Sanchez, Marvin X, Ron Milner, Woodie King, Jr., Bill Gunn, Ed Bullins, and Adam David Miller.Black Arts theater proudly emphasized its activist roots and orientations in distinct, and often antagonistic, contradiction to traditional theaters, both Black and white, which were either commercial or strictly artistic in focus.By 1970 Black Arts theaters and cultural centers were active throughout America. The New Lafayette Theatre (Bob Macbeth, executive director, and Ed Bullins, writer in residence) and Barbara Ann Teer's National Black Theatre led the way in New York, Baraka's Spirit House Movers held forth in Newark and traveled up and down the East Coast.The Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) and Val Grey Ward's Kuumba Theatre Company were leading forces in Chicago, from where emerged a host of writers, artists, and musicians including the OBAC visual artist collective whose "Wall of Respect" inspired the national community-based public murals movement and led to the formation of Afri-Cobra (the African Commune of Bad, Revolutionary Artists).

1516276800000

Cultural Fabric: The Maasai's Shuka

by Nellie Haung | G Adventures Even if you’ve never heard of cloth, there’s a high chance you’ve seen it in pictures. Often red with black stripes, cloth is affectionately known as the “African blanket” and is worn by the Maasai people of East Africa.To give you some brief background knowledge, the Maasai are a semi-nomadic people from East Africa who are known for their unique way of life, as well as their cultural traditions and customs.Living across the arid lands along the Great Rift Valley in Tanzania and , the Maasai population is currently at around 1.5 million, with the majority of them living on the Masai Mara National Reserve of Kenya. They are known to be formidable, strong warriors who hunt for food in the wild savannah and live closely with wild animals.The Maasai identity is often defined by colourful beaded necklaces, an iron rod (as a weapon) and of course, red cloth. While red is the most common colour, the Maasai also use blue, striped, and checkered cloth to wrap around their bodies. It’s known to be durable, strong, and thick — protecting the Maasai from the harsh weather and terrain of the savannah. Shuka’s originsSo how did this traditional clothing come about?The word “traditional” must be taken with a grain of salt. Before the colonialization of Africa, the Maasai wore leather garments. They only began to replace calf hides and sheep skin with commercial cotton cloth in the 1960s.But how and why they chose shuka cloth is still unclear today. There are a few schools of thought. One of them is traced back through centuries — fabrics were used as a means of payment during the slave trade and landed in East Africa, while black, blue, and red natural dyes were obtained from Madagascar. There were actually records of red-and-blue checked “guinea cloth” becoming very popular in West Africa during the 18th century.

1516234488000

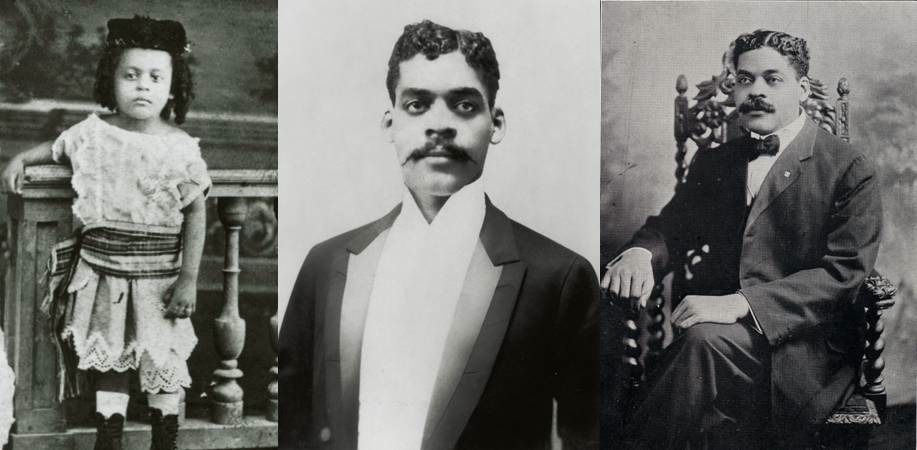

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg:Afro-Puerto Rican Writer, Historian, Activist

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, writer, activist, collector, and important figure of the Harlem Renaissance was born in Saturce, Puerto Rico. His mother, a black woman, was originally from St. Croix, Danish Virgin Islands (now the U.S. Virgin Islands), and his father was a Puerto Rican of German ancestry. Schomburg migrated to New York City, New York in 1891.Very active in the liberation movements of Puerto Rico and Cuba, he founded Las dos Antillas, a cultural and political group that worked for the islands’ independence.After the collapse of the Cuban revolutionary struggle, and the cession of Puerto-Rico to the U.S., Schomburg, disillusioned, turned his attention to the African American community.In 1911, as its Master, he renamed El Sol de Cuba #38, a lodge of Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants, as Prince Hall Lodge in honor of the first black freemason in the country.

1514336434000

Queen Sophia Charlotte: First Black Queen of England (Great Britain and Ireland)

Princess Sophie Charlotte was born on this date in 1744. She was the first Black Queen of England. Charlotte was the eighth child of the Prince of Mirow, Germany, Charles Louis Frederick, and his wife, Elisabeth Albertina of Saxe-Hildburghausen.In 1752, when she was eight years old, Sophie Charlotte's father died. As princess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Sophie Charlotte was descended directly from an African branch of the Portuguese Royal House, Margarita de Castro y Sousa.Six different lines can be traced from Princess Sophie Charlotte back to Margarita de Castro y Sousa. She married George III of England on September 8, 1761, at the Chapel Royal in St James’s Palace, London, at the age of 17 years of age becoming the Queen of England and Ireland.The conditions of the marriage contract were, ‘The young princess, join the Anglican church and be married according to Anglican rites, and never ever involve herself in politics’.Although the Queen had an interest in what was happening in the world, especially the war in America, she fulfilled her marital agreement. The Royal couple had fifteen children, thirteen of whom survived to adulthood. Their fourth eldest son was Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent, later fathered Queen Victoria.