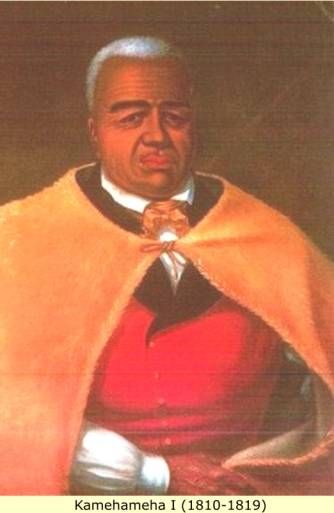

King Kamehameha I (1810-1890)

The Kamehameha royal family of Hawaii, ca. 1853. Left to right: Kamehameha III (center) and his wife, Queen Kalama (right); Kamehameha IV (right rear), Kamehameha V (left rear) and their sister, Victoria Kamamalu (left).

Hawaii: Black Royalty in the Pacific

Setting aside their bigotry, the Southern settlers hit upon a fact which is studiously ignored by modern anthropologists and historians: the natives of Hawaii, America’s 50th State, were Black people whose ancestral roots extend back to the continent of Africa.The story of the Black Hawaiians is one of the most tragic of modern times.

It is a tale of adventure and gaiety in paradise that turned into a cultural nightmare. It is America’s best kept secret. We must venture into antiquity to learn of the roots of the Black Hawaiians, whose glorious star, now vanished from the Heavens, once brightened the Pacific for two thousand years.

Most anthropologists, paleontologists and archaeologists around the world generally believe that human beings evolved on the continent of Africa, from 3 to 5 million years ago, and that they eventually spread from Africa into Europe, Asia the Pacific Islands and finally the Americas.

In time, these Black settlers developed very advanced societies that sent navigators to explore and settle various islands of the Pacific Ocean. They reached such places as New Guinea, Fiji, New Hebrides, New Zealand, the Society Islands, Tahiti, Easter Island and thousands more.

The first people to reach what is now Hawaii were Blacks from Polynesia – a name which means “many islands” – in the central Pacific. They sailed to Hawaii in giant canoes about 2,000 years ago.

The Hawaiians and their neighbors in the Pacific have long been the subject of controversy among scientists. The people in this part of the world are generally divided into three groups: Melanesians (the word means black islands), who are unmixed Black people; Micronesians (which means small islands), an ancient Black people who are now largely mixed with Asians; and Polynesians, a people who were also originally Black but have mixed historically with Asian Mongoloids and White Europeans.

Black Roots A Puzzle

The Black people themselves are an ethnological puzzle. Many like the Tasmanians, who were exterminated by English settlers were “pure” Blacks. The Australian Aborigines were also very dark with African features and curly hair.“The basic strain of the original Hawaiians, as seen in their color and their faces,” writes historian J.A. Rogers in Sex and Race: Negro-Caucasian Mixing In All Ages and All Lands, “was undoubtedly Negro, with an admixture of mongolian.

”These people were of black and brown complexions with wavy or close-curled hair, broad facial features and fine physiques. In short, they had the same physical characteristics as millions of other people who now live in the Pacific Islands.

According to one early legend, these early settlers named their new home Hawaii in honor of a chief named Hawaii-Loa, who is said to have led the Polynesians to the islands. But the name Hawaii is also recognized as a form of Hawaiki, the legendary name of the Polynesian homeland to the west.

The ancient land of Hawaii was much like an African society. It was a series of islands ruled by strong-willed chiefs or kings who believed that they had descended from gods. No written records of the islands were maintained, so a court genealogist, similar to the African griot, recited names, family exploits, battles and past glories of a proud people and their royal leaders. Hawaiian life revolved around religious ceremonies.

The heiau stone platforms, generally enclosed by stone walls, served the Hawaiians as temples. Inside these centers of worship were a number of objects for ceremonial use in various rituals. They were used on numerous occasions, for to the Hawaiian people any new undertaking in life was cause for religious celebration. The principal Hawaiian gods were Kane (life), Lono (harvest) and Ku (war).

Queen Liliʻuokalani, born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Wewehi Kamakaʻeha, was the last monarch and only queen regnant of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The Queen ascended the throne on January 29, 1891.

King Kalākaua, born David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Mahinulani Nalaiaehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua, was the last reigning king of Hawaii. He was succeeded by his sister, Queen Liliuokalani.

SKU00004

SKU00005

SKU00006

Closely linked to Hawaiian religious traditions was the kapu or law administered by the king. It was a rigid system of “rules and guides, do’s and dont’s, what’s and what-not’s” governing events from love-making and marriage to the season for catching certain fish.

It separated kings from commoners, men from women, and Hawaiians from foreigners. It was probably one of the most complex legal systems of the ancient world.

Heaven on Earth

If ever there was a paradise on earth, the Hawaiians appear to have had it. Blessed by a glorious climate, the people basked in the sun, swam in clear water, and participated in competitive games and sports.

They worked, to be sure, in order to live; but there was a fine line between work and play.

Fishing, for example, was probably as much a water sport as a source of obtaining food.

The people shared their harvest so that no one was without food, and everyone found shelter in the marvelous huts built mainly from the leaves of palm and Hala trees.

“The people worked, swam, sang and danced, isolated from most of the scourges of the rest of the world,” writes Maxine Marantz in Hawaiian Monarchy, The Romantic Years.“But that was soon to be changed. The ‘Garden’ would be discovered.

“Gone would be the sunny static days of peace and order. Disease, decadence, and cultural shock were to take a terrible toll on the Hawaiian people, decreasing their numbers alarmingly.”

This great change, however, was still far off in 1758, which was about the time of the birth of Kamehameha, nephew of King Kalaniopuu who ruled the island of Hawaii and the Hana district of the island of Maui.

At this time Hawaii was not ruled by a single king but was a chain of islands (Kauai, Maui, Oahu, Hawaii, Molokai, Lanai, Niihau, and Kahoolawe), each ruled by a different monarch.

Gun Control

Kamehameha I had gained control of Hawaii because of his use of firearms, obtained from white traders; and during his reign, he relied on the advice of two captured British sailors, John Young and Issac Davis. They served as his political and military intermediaries, dealing with rival chiefs and a growing number of foreigners.

It was probably because of the influence of his advisors that Kamehameha did not readily detect what was happening to his country. Honolulu Harbor began receiving many foreign ships.

Trade flourished as foreigners brought goats, geese, horses and turkeys, as well as trees and fruits. Hawaii gradually became one of the major trading centers of the Pacific; but the Black masses, who had never known disease, were rapidly being destroyed by venereal disease; and those who escaped this affliction, generally fell prey to liquor and firearms.

To the rescue came hundreds of White missionaries following the death of Kamehameha I. In a misguided frenzy, these foreigners began an assault on the Hawaiian culture that ultimately led to a complete demoralization of the native people and paved the way for the loss of their land.

King Kamehameha II (1797-1824) followed his father to the throne. His reign was short and tragic. He was weak of character, yielding largely to the demands of local chiefs and foreigners and following the general dictates of his mother, the fearless dowager queen, Kaahumanu, whom he permitted to share the throne with him.

Despite the fact that the young king could not match his father’s greatness, he and Queen Kaahumanu did manage to overthrow the Kapu system, which had for centuries caused problems between the various classes of Hawaiian people. King Kamehameha II and his young wife died of measles, a disease totally alien to them, while on a tour of England in 1824.

Their unexpected deaths may well have been an omen, for soon thereafter the near-death of Hawaiian culture came during the 30-year reign of Kamehameha III (1814-1854), Hawaii’s third ruler.

At the outset, the king, highly disturbed by the general drift away from Hawaiian traditions, attempted to revive many of the ancient pastimes, including the hula, in an effort to restore the original power of the king and to return Hawaii to what it was under Kamehameha I.

This did not work. So successful had the missionaries become in Hawaii that both Queen Kaahumanu, the widow of Kamehameha I, and Kinau, the queen’s successor, would not tolerate the new king’s attempted revisions.

They supported a code based on the Ten Commandments and encouraged the general westernizing of Hawaiian culture.

Foreign Takeover

Kamehameha III was very sensitive to the needs of the Hawaiian people. While he resented the encroachment of foreign missionaries and traders, the king gradually came to realize the permanence of their presence and thereafter sought their guidance in improving the status of his people

The king and his wife, Queen Emma, frequently entertained foreign dignitaries; yet he discouraged the participation of missionaries and foreigners in his government.

Deeply concerned about the mounting death rate of Hawaiians due to the influx of foreigners carrying strange diseases, Kamehameha IV and his wife collected enough pledges and subscriptions from their friends to finance a hospital in 1859. But the king was unable to complete his work because of his untimely death at the young age of 29.

His brother Lot Kamehameha (Kamehameha V: 1830-1972), then came to the throne. He was the true spiritual son of Kamehameha I. A man of broad background, boundless energy and remarkable ability, he favored an aristocratic monarchy over the constitutional monarchy that had prevailed from the time of Kamehameha III.

During the reign of Kamehameha V, Hawaiian ties with America– whose missionaries and businessmen were becoming more and more prominent in Hawaiian affairs – were loosened and the islands experienced a radical change of their economy as whaling, the prime industry, lost its place to sugar.

Kamehameha V died on December 11, 1872. He was succeeded by King Lunalilo (1835-1874). Known to all as the “People’s King,” he was the first elected king in Hawaiian history and enjoyed the love and respect of his people.

His short reign of a little more than a year was marked by an effort to liberalize the constitution, attempts to curb the spread of leprosy, the appointment of a new board of health and an unsuccessful plan to cede Pearl Harbor to the United States. The young king died of tuberculosis on February 3, 1874.

King Kalakaua (1836-1891) succeeded King Lunalilo. While somewhat capricious and given to frequent drinking, this, the seventh ruler of Hawaii, was a scholar, poet and musician. He also traveled extensively. During his reign, the king reserved the leading administrative posts in his government for native Hawaiians.

Indigenous Hawaii and Fiji islanders in traditional clothing.c. 1890

Mataio Kekuanao‘a, high chief of the island of Oʻahu with his daughter, Victoria Kamamalu, Kuhina Nui (regent or prime minister) of Hawaii and its crown princess, c. 1850.

A young Queen Liliʻuokalani, the last reigning monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

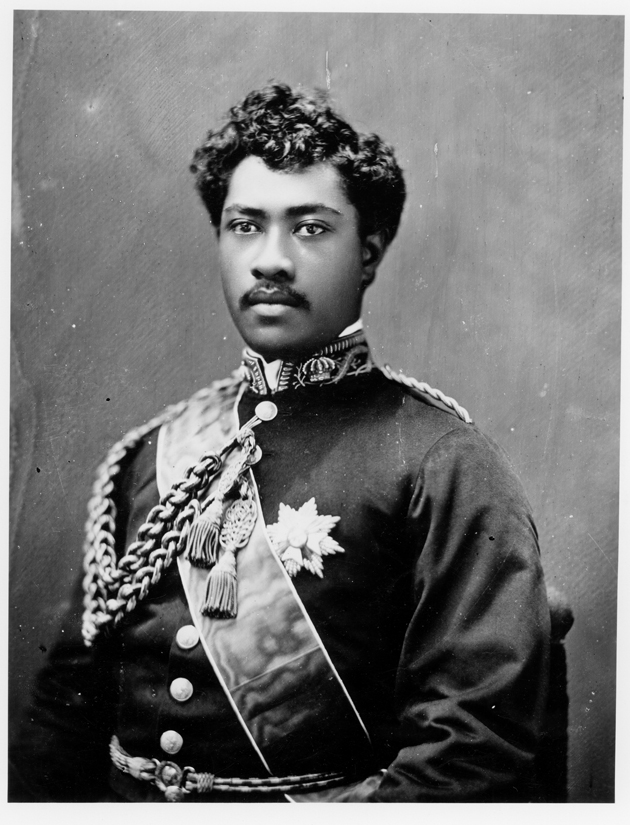

Prince Leleiohoku II of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and member of the reigning House of Kalākaua.

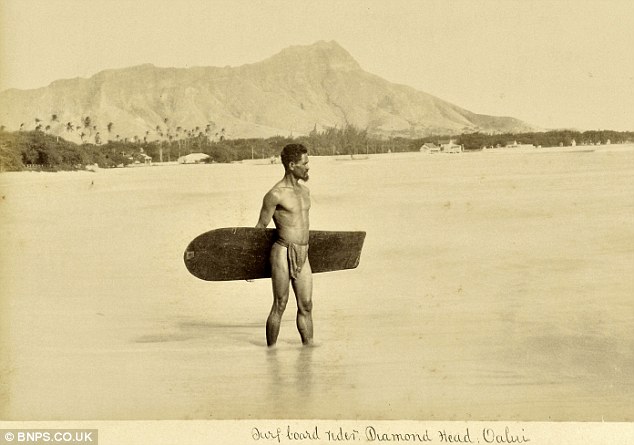

Muscular Hawaiian surfer c. 1890 wearing a traditional loin cloth. After 1789 missionaries virtually stamped out all surfing in Hawaii because they thought it ungodly.

Hawaiin women c. 1890

Last Black Queen

The last native ruler of Hawaii was the celebrated Queen Liliuokalani. Following the queen’s ascension to the throne on January 29, 1891, a Chicago newspaperwoman, Mary H. Krout, described Liliuokalani as “strong and resolute. The features were strong and irregular. The complexion quite dark; the hair streaked with gray, and she had the large dark eyes of her race.”

The queen was a brilliant writer, poet and composer who worked tirelessly for the welfare of her people. While she sought to strengthen the monarchy and literally return “Hawaii to the Hawaiians,” the queen was years too late.

American businessmen and missionaries now had strongholds in every corner of Hawaiian culture and were redoubling their efforts to overthrow the monarchy and to place Hawaii under a provisional protectorate. By the last part of 1892, these plans were carried out and the U.S. Marines were placed around the royal palace.

The queen stood steadfastly against the U.S. forces but finally, on January 17, 1893, she yielded under protest, as was recorded in the “Pacific Commercial Advisor” of January 18:

I, LILIUOKALANI, by the Grace of God and under the Constitution of The Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the Constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a Provisional Government of and for this Kingdom.

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do under this protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall upon the facts being presented to it undo the action of its representative and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

Statehood

The United States never chose to “undo the action of its representative.” In fact, by 1900 Hawaii had become a territory of the United States and a state by 1959. From King Kamehameha to Queen Liliuokalani, each Hawaiian ruler was very dark-skinned with Negroid features. It is one of the incredible ironies of history that few Americans are aware that the original Hawaiians were black people; and that their royal family was one of the greatest of the 19th Century.

The destruction of these people and their culture and the forceful annexation of their land were tragedies of staggering proportions and a sad chapter in the history of the United States. This probably explains why the true story of Hawaii remains until this day America’s best-kept secret.

By Legrand H. Clegg, II

Suggested Readings

In 1780, before a council of chiefs, King Kalaniopuu officially named his older son, Kiwalao successor to his throne. But this was not to be. Kamehameha coveted the throne and set out to do all in his power to become king.

Following the death of King Kalaniopuu, Kamehameha aligned himself with a number of chiefs in a battle against his cousin Kiwalao.

Kamehameha defeated Kiwalao and thereafter proceeded to battle against the chiefs of Maui, Lanai and Molokai. By 1810, King Kamehameha was the first to rule all the islands. Six other kings and a queen would succeed him to the throne.

Generally described as very dark and “extremely handsome,” Kamehameha (or Kamehameha, The Great, as he is often called) was a very capable ruler.

He encouraged industry, promoted international trade, checked oppression, and suppressed crime.

His greatest drawback, however, turned out to be the faith he had in Europeans. Captain James Cook was the first white man to reach Hawaii. He visited the islands in January of 1778, traded with the natives, and was well treated.

After returning to Hawaii in November of 1778 and remaining into the next year, he was killed when a quarrel arose between his traveling companions and the Hawaiians.

It was with the help of foreigners that the king established free schools throughout the islands, introduced Hawaiian language newspapers, and drafted the first Hawaiian constitution.

Kamehameha III’s greatest achievement, however, can be found in his institution of land reform, called “The Great Mahele,” or land division, which permitted commoners to share in the land that had previously been the exclusive property of the king and his clients.

In 1855, Alexander Liholiho, the adopted son of Kamehameha III, succeeded him to become Kamehameha IV. A brilliant monarch, his court was run with elegance and style. At the outset, the king, highly disturbed by the general drift away from Hawaiian traditions, attempted to revive many of the ancient pastimes, including the hula, in an effort to restore the original power of the king and to return Hawaii to what it was under Kamehameha I