John-Michel Basquiat: The Afrofuturistic and His Art

Part I - Cosmic Slop and George Clinton's Afro-Futurism

"I’ve never been to Africa. I’m an artist who has been influenced by his New York environment. But I have a cultural memory. I don’t have to look for it; it exists. It’s over there, in Africa. That doesn’t mean that I have to go live there. Our cultural memory follows us everywhere, wherever you live.”

-Jean-Michel Basquiat

While attending college in the early 1970s, the “message in the music” was important. Socially-conscious black music introduced a new black vernacular, innovative technology, and inspired visual iconography. Message music and stunning album covers belong to the Black Arts Movement (1968-1978). My aesthetic tastes expanded beyond the rhythmic sounds of Motown (Temptations, Miracles, Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye and Jackson Five) and the throbbing beats of Polydor Records (James Brown).

Well, sort of. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Brown continued to crank out the hits. They conjured enchantment. His extended album songs—beginning with 45s covering both A & B sides—set the stage for future musicians, including Hip-Hop artists.Record companies exploited black cultural production and mass-marketed Brown’s songs to young people who seemingly wanted to dance forever (I am not unaware that aficionados credit the Jamaican artist Lee “Scratch” Perry with inventing long play records).

Not unlike Brown’s live album “Sex Machine” (1970), his studio produced albums (“The Payback,” 1973, featuring “The Payback,” and “Hell,” 1974, featuring “Poppa Don’t take No Mess”) kept us dancing, whooping, hollering, and channeling lyrics through improvised call and response chants while we worked up a sweat. By 1985, films like Jamie Lee Curtis’s “Perfect” transformed his syncopated beats and set them to aerobics dance music. Brown’s album cover illustrations weren’t bad either. His creative legacy is undeniable.

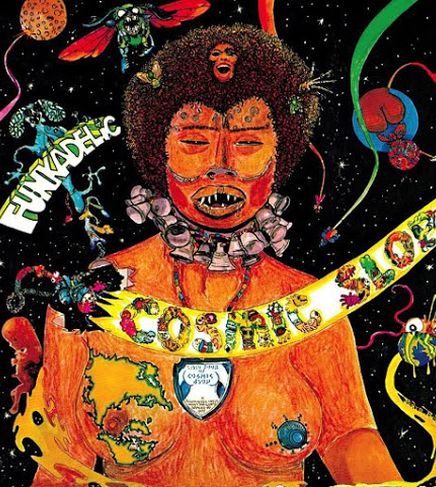

During this period, a black-rock group called Funkadelic, organized by George Clinton, took it to the stage. Funkadelic followed the Afro-futurist sensibilities of Jazz visionary Sun-Ra and Lee Perry.

In its evocations of space-ships, extraterrestrials, and ancient Egypt, Funkadelic built upon complex mythologies of social alienation associated with the African Diaspora. Afro-futurism’s intellectual history shows how its producers creatively explored the relation of technology to the black arts.

Funkadelic was the sister act of Parliament, a funk and soul dance band. Many of the musicians played for both groups. By 1975, the majority of James Brown’s band (polished, old-school jazz and rhythm-bluesmen) decamped for George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic lineup.

Clinton, a musical genius, was not alone: other groups, including but not limited to Earth, Wind and Fire, Cameo, and Dexter Wanzel (and later, Hip Hop artists led by Afrika Bambaataa) embraced the Afro-futurist philosophy.

Futuristic blackness was in.

The impact of the Afro-futuristic on New York artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, especially Clinton’s impact, has not been given due credit (fig. 1). This essay is not only about his impact.

It is also about the Black Arts Movement’s long-term effect on social and cultural exchange. Basquiat’s art frames a turbulent, tragic, and inspiring world composed of images and texts that defines his themes of “royalty, heroism and the streets.”

His heroic blacks included athletes, prophets, gods and goddesses, warriors, cops, musicians , kings and self portraits. The years between 1981 and 1982 are considered Basquiat’s “first period, a critical phase in his career.” By 1983, the young artist made his first significant gallery exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

His mercurial rise to international stardom followed. Basquiat, a hot commodity, had paintings selling for as much as $10,000.00 apiece. The middle phase of Basquiat’s career witnessed an interest in Pop Art. By 1984, Basquiat was collaborating with famed Pop Culture artist, Andy Warhol. In 1985, Basquiat posed for the cover of the New York Times Magazine. It appeared with a long article titled “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist.”

By 1987, Basquiat was painting black musicians, black popes, and ominous self-portraits. Even as his career soared, writes historian Jeff Chang “his demons would not rest.” Fame and the ambivalence of the art establishment proved too much: Basquiat died on August 12, 1988, of a heroin overdose at his New York City art studio. He was 27.

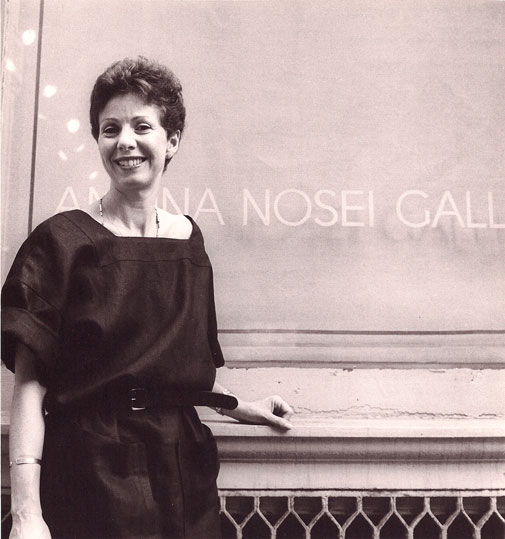

Annina Nosei, helped to fashion Basquiat's art pedigree (fig. 2)

Art historians gush over his white artistic influences: Leonardo Da Vinci, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Cy Twombly and Franz Kline figure prominently. No argument here. The western art tradition, jealously guarded by a ‘high art’ priesthood, had to justify Basquiat’s membership. Basquiat, no dummy, wanted fame.

Celebrity required cultural legitimacy, an artistic heritage defined by the western art canon. His first dealer, Annina Nosei, helped to fashion his art pedigree (fig. 2). Basquiat was complicit in this action. “Picasso” writes Dick Hebridge, could afford to leave the marketing and manufacturing of the iconic self to future generations.” Not so for Basquiat. His blackness remained an issue. Luca Marensi writes: “The use of some imagery, specifically black or African, leaves no trace that would allow an uninformed viewer to suppose the painter is black.”

Art writer Glenn O’Brien described the young Basquiat as “alarmingly autodidactic.” O’Brien wrote, “There’s a traditional science fiction scene in which the superior alien, or robot, decides to learn the entire contents of our culture [my italics; white] at one sitting, usually in front of a computer terminal or television. He was like that. He absorbed paintings, films, record albums and books like some kind of bionic recording device.” This view recalls racist stereotypes of blacks as imitative creatures. O’Brien’s Afro-Alien, Basquiat, was a tortured soul.

Such views—there are others—found little need to contemplate the relation of racial identity to Basquiat’s work. Art-for-art’s sake mystification ripped him asunder. Black artistic influences are relegated to a cultural backwater.

They are, in my view, seminal.

This essay begins with an unsung period: the late 1970s. During his early days, Basquiat became keenly aware of the black condition and black cultural production. The aspiring artist recreated this black world in his own image. He was not only a prolific artist, but a Creator-Destroyer that embraced concepts employed by unsung ancient and modern black heroes. I will examine a small selection of his work, taking special interest in these inheritances.

Cosmic Slop: Comics and George Clinton’s Afro-Futurisism

Ahhh, ahh-ah-ahhhhh, hear my mother call / I was one of five born to my mother / An older sister and three young brothers / We've seen it hard, we've seen it kind of rough / But always with a smile, she was sure to try to hide / The fact from us that life was really tough

Excerpt from Funkadelic’s “Cosmic Slop”

In 1960, Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York. His parents, Matilda Andrades and Gerard Basquiat, had four children. His father was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti; his mother, of Afro-Puerto Rican descent, was born in Brooklyn. Jean-Michel was a prodigy.

He enjoyed books and comics, music, sports (baseball and boxing), television and films, and art. He dreamed of becoming a comic book artist. His mother, “a very good artist,” encouraged him, taking Basquiat to museums and enrolling him as a junior member of the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Basquiat mastered French, Spanish and English.

He spoke, read, and wrote these languages fluently.

In 1968, a car struck Basquiat and the eight year-old had his arm broken and suffered internal injuries. His spleen was removed. During hospital rehabilitation, his mother bought him Gray’s Anatomy, an illustrated scientific volume on the study of the human body. He absorbed its contents. His parents separated that same year. Gerard Basquiat raised the children.

George Clinton’s song “Cosmic Slop” (1973), is as good a metaphor and allegory as Gray’s Anatomy (fig. 3)

Trauma: some art critics imagine his spleen as an allegorical wound; Gray’s Anatomy being a symbol of Basquiat’s turbulent life. In 1974, the family moved from Brooklyn to San Juan, Puerto Rico. In 1975, his mother suffered a mental breakdown and was institutionalized. Two years later, Basquiat’s family returned to New York.

His poor relationship with this father forced the teenager to run away from home. He hung out with friends, experimented with drugs, and slept on park benches. In 1976, Basquiat rebelled against teachers and dropped out of high school.

After his father disowned him, the teenager prophesized that he would become famous. Troublesome times indeed. Basquiat’s later appropriation of the graffiti tag (nickname), “SAMO,” seemed proper. According to one account, it means “Same Old Shit.”

George Clinton’s song “Cosmic Slop” (1973), is as good a metaphor and allegory as Gray’s Anatomy (fig. 3). Clinton narrates the story of a troubled black family.

In order to help make ends meet, an impoverished mother with five children takes to the streets. She resorts to prostitution. The mother also attempts to shield her children from their dire circumstances. Every night she begs for God’s forgiveness and understanding.

Of course, this “sad, bluesy song” bears no reflection on Basquiat’s mother. Rather, it conveys ubiquitous challenges facing the black urban community. Clinton’s Afro-futurism bears literal and symbolic significance for Basquiat’s artistic production.

Grand ideas out of little details: Basquiat’s Afro-futurism also owes a debt to the Chicago artist Pedro Bell. Critics describe Bell as “an urban Hieronymus Bosch”; his imagery “sublime and hideous to jarring effect.”

Bell singlehandedly defined the Parliament-Funkadelic science-fiction “superheroes who fought the ills of the heart, society, and the cosmos.”

As an art student, I became acquainted with Bell’s work via his brother, Bruse Bell, a fraternity brother. Bruse, an artist as well, assisted Pedro in creating Funkadelic covers.

Both exhibited a style that paved the way for black underground comix. For dances and other events, I readily adopted his brand of Afro-futurism and infused the iconography into my posters and flyers. Pedro influenced many aspiring black artists.

Basquiat loved Parliament-Funkadelic. He credited George Clinton’s layering of sound to his own layering of visual images. Annina Nosei, his dealer, complained about his music blaring from Basquiat’s basement studio; Nosei providing free space.

The rock sound combined with psychedelic drugs, LSD, became part of his scene. (When the German writer Isabelle Graw queried if he used drugs in order to paint, Basquiat angrily retorted “I don’t think my paintings look as if they were done under the influence of drugs.” Of course, Graw wouldn’t have insulted a white artist.)

Basquiat unquestionably crossed paths with Clinton. A contemporary photograph shows Clinton and Madonna, one of Basquiat’s friends (fig. 8). Whether he met Pedro Bell, I cannot say.

Between 1968 and 1978, black artists, writers and musicians embraced a concept of self-determination through creative self-expression. This demand became a dominant theme; the era heralded the Black Arts Movement. It was a messianic moment. According to black art historian Samella Lewis, contemporary artists did not hesitate to use diverse ideas and techniques in the production of art forms that spoke to black people. They deployed, writes Lewis “Social Realism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Conceptual Art, [and] other popular styles.”

“Subject matter and philosophical orientations [were] also diverse, though for many Black artists in America, Africa [served] as the principle source of creative inspiration.” This new consciousness in the process of realization returned to the Afro-futuristic sensibility as a valid aesthetic principle as well.

Basquiat’s work took for its inspiration subjects that were absent from the walls of traditional museums. It explored African culture and celebrated the black cultural heritage. It took inspiration from modern black urban life. It celebrated historical figures and heroes of the black community. National issues relative to the black community inspired his work as well.

In 1978, the eighteen year-old Basquiat created a comic book titled “What?” Its subtitle, “Sex, Violence, Drugs and Fun,” is apropos (figs. 4-5). Janet and Steve, two lovers making out in a car, overhear an explosion. They wonder as to its source. After taking Janet home, Steve returns to discover a UFO crash site. As his car radio blares Little Richard’s 1958 song “Good Golly, Miss Molly,” the downed Mother Ship ejects two small orbs.

From them, like Russian puzzle dolls, two shadowy human forms emerge. Steve’s lechery gets the best of him. An Afro-Alien enchantress induces the drooling man to say “Zeno.” The incantation causes a violent end: it propels Steve from his vehicle. The extraterrestrials take his car and head toward New York City. Speeding along the highway they pass a billboard advertising “SAMO Studios.”

Behind it lies Steve’s lifeless form.

Basquiat enjoyed science fiction films. “What?” recalls the 1956 sci-fi classic “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” Basquiat undoubtedly saw the 1978 remake. Both films are about the alien cloning of humans (Clinton’s “Dr. Funkenstein” motif).

What makes “What?” different is black extraterrestrials, something absent from early sci-fi films. His creatures—devoid of human sentiment—adapt characteristics, memories, and personalities of earthlings in North America. Basquiat’s 1950s soundtrack effectively frames his black horror/comedy. Corny and predictable, the storyline has B-movie written all over it. An Afro-Alien vehicle with dark-skinned extraterrestrials crashes to the earth.

In page one’s third panel, a brown hand presents to the beholder a text in an alien tongue. The translation: “We’ve arrived.” While their intentions remain unclear, earthly transformation and earthly transportation set an ominous tone.

Basquiat’s oeuvre reveals an avid admirer of cartoons and comic books. They spurred his creative imagination. His alien invasion narrative riffs several sources. The text recalls “Zap Comix,” an underground comic book genre created by Robert Crumb. Bulky, organic, and reedy lettering resonate with Crumb’s style.

Page eight is an ode to Crumb: the word “Zap!” overlaps a thunderbolt. A burning marijuana cigarette resting in an ashtray—not unlike inanimate objects in Crumb’s work—displays the magical quality of engaging in human thought. Crumb’s dated images of brawny, long-haired women intrude into Basquiat’s work.

She wears a sleeveless shirt, daisy duke shorts and high boots. She’s a “biker chick,” tough and threatening. For Crumb, such women are sexual fantasies. Critics argue that Crumb’s female caricatures, white and black, are misogynistic and racist. A valid claim, for sure. Crumb depicts overtly violent sexual scenes (fig. 6).

From a black perspective, his obsession with black folk, blues and jazz music, remains to be seriously studied. Another source is Peter Max, an artist who reached his apex of popularity in the 1970s (fig. 7).

Max’s art is beautiful. His art nouveau-styled lettering, decorative ornamentation, whimsical lines, and airy figures possess an ethereal quality. In high school, I enthusiastically copied his newspaper cartoons. However, I transformed his white characters into black ones. Basquiat incorporated Max’s decorative style into his art.

Grand ideas out of little details: Basquiat’s Afro-futurism also owes a debt to the Chicago artist Pedro Bell. Critics describe Bell as “an urban Hieronymus Bosch”; his imagery “sublime and hideous to jarring effect.” Bell singlehandedly defined the Parliament-Funkadelic science-fiction “superheroes who fought the ills of the heart, society, and the cosmos.”

As an art student, I became acquainted with Bell’s work via his brother, Bruse Bell, a fraternity brother. Bruse, an artist as well, assisted Pedro in creating Funkadelic covers. Both exhibited a style that paved the way for black underground comix. For dances and other events, I readily adopted his brand of Afro-futurism and infused the iconography into my posters and flyers.

Pedro influenced many aspiring black artists.

Basquiat loved Parliament-Funkadelic. He credited George Clinton’s layering of sound to his own layering of visual images. Annina Nosei, his dealer, complained about his music blaring from Basquiat’s basement studio; Nosei providing free space. The rock sound combined with psychedelic drugs, LSD, became part of his scene. (When the German writer Isabelle Graw queried if he used drugs in order to paint, Basquiat angrily retorted “I don’t think my paintings look as if they were done under the influence of drugs.” Of course, Graw wouldn’t have insulted a white artist.)

Basquiat unquestionably crossed paths with Clinton. A contemporary photograph shows Clinton and Madonna, one of Basquiat’s friends (fig. 8). Whether he met Pedro Bell, I cannot say.

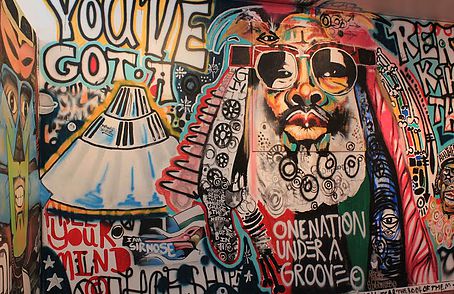

A graffiti painting pays homage to George Clinton and the “Mother Ship” (fig.9)

Little doubt the artist was impacted by Bell’s work. A graffiti painting pays homage to George Clinton and the “Mother Ship” (fig. 9). Self-referential Bell-sian nuttiness: Steve is Basquiat’s alter-ego. Both sport a brownish-yellow Mohawk hairstyle. Both love sex, rock-and roll, and cars. “SAMO” is emblazoned on Steve’s license plate and tire rims.

Highways, billboards, and roadside gas stations relate not only to the romance of car culture but also to eerily tragic events (remember Ingrid Steven’s “Twilight Zone” episode, “Going My Way?”).

They invoke film actor James Dean. In “Great American Dream Machines,” writer Jay Hirsh notes that Dean’s legend was cemented in Rebel Without a Cause. In the film Dean drove a 1950 Mercury Coup, “a macho car.” In 1955, Dean died while driving a 1955 Porsche Spyder. For Basquiat, a heroic life required guts. He once informed an interviewer, “I just want to live life like James Dean.”

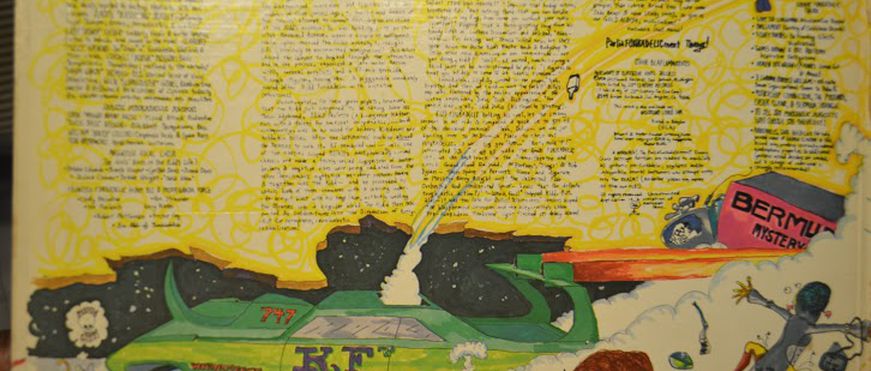

Bell’s interior album cover image, “Tales of Kidd Funkadelic” (fig. 10)

By James E. Brunson

One source for “What?” is Bell’s interior album cover image, “Tales of Kidd Funkadelic” (1976). Its text and image are illuminating (fig. 10). Kid-Funkadelic’s “Merricane Diablo Coupe” ejects a three-toed Afro-Alien and liquor bottle into space. The victim “is sent into a slow spiral, several hundred feet into the tripposphere.”

The “alleycruiser” discharges reddish flames and yellow smoke as it hurls toward “Chikkago.” It “phase-shifts through any dimensional happenins’ for coological and & nightly assorted jollifications.” Coological, indeed. According to Juxtapoz Magazine, Bell’s imagery and texts helped to form Parliament-Funkadelic’s conceptual dimension.

Text and image and layered and the seemingly meaningless plethora of data compels the viewer to decipher the artist’s intent. His work opened the door for all the great graffiti artists of the late 1970s. Basquiat was not immune.

James E. Brunson

Next Feature - Part II - SAMO Days: Young Bohemians, Radical Chic and Blackness