Black Broadway and Off Broadway Shows You Must See

A shockingly low number of women writers of color are presented on stages across America. Looking at regional theatres across the country in the last three theatrical seasons, only 3.8% of plays were written by a woman of color according to .

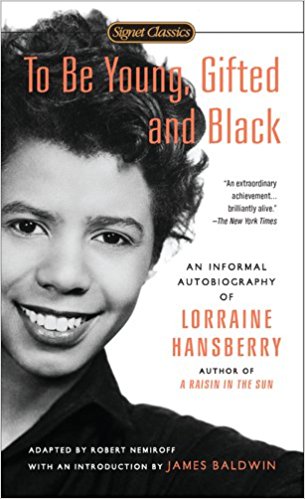

Here in Seattle in fall 2016, we saw the tides begin to change as three theatrical organizations produced works by black women playwrights: with Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White (culminating their full summer season celebrating black women playwrights), with A Raisin in the Sun, and our own contribution, with The Wedding Gift.

While this is a triumph for Seattle, a great, progressive city, we must continue pushing forward as a nation. Our work will not be done until we allow artists of color the same opportunities to share their thoughts and explorations on any subject within the human experience, not just what we deem them to be through the lens of their race.

This freedom to tell stories about the complex whole of humanity is a privilege that has been reserved for the mostly white men who have commandeered our stages for so long.

Here’s the thing: it’s hard enough just writing a damn play. But when you’re a white playwright writing about white people, you don’t have to also worry about your socio-political responsibility to white people, whether you’re representing them accurately or in a way that they’ll find acceptable.

You don’t have to worry about whether you’re reinforcing white stereotypes. You don’t have to worry about how people who are not white will receive your work, or wonder if the non-white theatre critic at your local paper has been exposed to enough white culture to “get it.”

There are little to no Asian-American theatre critics at most major theatre reviewing papers in the country. Hardly any black, Latino, or Native-American ones come to mind either.

Playwrights of color have to consider this every time they sit down and stare at that blinking cursor. Compound that by throwing gender into the mix, and it’s downright exhausting. Which is why it’s understandable if they would refuse to get bogged down by all of it and focus on something other than race or gender in a work.

Like the tragic loss of a friend (Ngozi Anyanwu’s Good Grief), the emotional brutality of mothers-in-law (Nandita Shenoy’s Washer/Dryer), or the cut-throat culture of academia (Merit by Lenelle Moïse).

Sometimes, women writers of color just want to focus on being human for a while and forget that there’s a whole country full of people who subscribe to the Steve King “sub-group” school of thought when it comes to people who aren’t white men.

And that “sub-group” mentality? It affects not just the playwright’s creative process, but how the products of that process are viewed as well. White people’s expectations for the work of writers of color present a damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t dilemma.

On the one hand, heaven forbid a writer of color choose not to have race be the focus of a work. For example, A. Rey Pamatmat’s play Edith Can Shoot Things and Hit Them—a critic said of the Filipino-American characters that he wished “more of their culture were on display,” and thought it was “odd that they have no racial problems.”

It’s as if it’s Pamatmat’s responsibility to educate non-Filipinos about Filipino culture, and not simply craft a narrative that appeals to people’s souls. Though seemingly white audiences pretty much demand that writers of color write about race, many lack the cultural frame of reference to receive it.

Take for instance, Dominique Morrisseau’s Detroit ’67. Here’s a play about a black family dealing with the appearance of a white stranger in distress during the Detroit race riots. You know. The 1967 riot. Fires. Violence.

Them Speak: It’s Time to See More Works from Women Writers of Color on Stages Across America

By Sola Chisa Hutchinson and Wesley Frugé

High hostility. One white critic who reviewed it likened it to Good Times. Because that’s the extent of his exposure, and his entrée into black culture did little to prepare him to receive the nuances in Morrisseau’s play.To complicate matters, one can’t help wondering how these plays would’ve been received had they been written by Stephen Adly Guirgis or Bruce Norris, both white men who have been rewarded for presenting narratives about black and brown people.

Suggested Readings

Edith Can ShootIt’s likely any degree of cultural exhibitionism would have deemed Edith Can Shoot Things bold and broad-minded. And it’s highly unlikely that a play set against such a tumultuous and racially charged backdrop as 1967 Detroit would have been compared to a ’70s sitcom.

While there will always be those who undertake the work of exposing and dismantling bigotry in their work, there are playwrights of color writing modern plays that are not about slavery or race relations in the mid-twentieth century.

It’s time to hear and see these plays on our stages right alongside those that do explore these important and, sadly still timely, topics.

And its long past time that works that do depict racial oppression and all the problems that come along with it have a proper context, in which they can be thoroughly and thoughtfully processed. When you go to the theatre and see a play, consider supporting the work of writers of color, especially women.

We are so rarely given the opportunity to hear their voices, and that must change if we are ever going to move forward as a unified nation. (Or at least not inspire riots by ticking off entire segments of the American population.)

Samantha Soule and Francois Battiste in Detroit ’67, directed by Kwame Kwei-Armah at the Public Theater. Photo by Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times.

This piece, "Let Them Speak: It’s Time to See More Works from Women Writers of Color on Stages Across America"by Chisa Hutchinson and Wesley Frugé was originally published on HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community, on January 14, 2017.

Dedra Woods and Tracy Michelle Hughes in Alice Childress’ Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White at Intiman Theatre. Photo by Chris Bennion.